As an executive search firm, we have led more than 100 searches to find CEOs for the world’s largest faith-based nonprofits. In every instance, there is a board who is strongly committed to the future of the institution, and in every instance, there is great intent to assure that the transition from the incumbent to the new leader is as accretive as possible to the mission of their organization.

Here are five mistakes that boards should work very hard to avoid:

1. Delegating Succession Planning to the CEO

Selecting the right leader is the most important responsibility of the board, and it should never be delegated to the incumbent leader. As competent as any leader may be, organizations benefit from new thought. The CEO’s choice does not give the board its needed influence over the future of the organization.

2. Committing the Role to an Internal Person

While an internal person may ultimately be the best selection, the board should not be restricted to a choice of one. As importantly, circumstances change and so do board members. It is unfair to use assured succession as a tool to retain a leader who may later be surprised by the board’s different direction.

3. Hiring in Reaction to the Incumbent

Most search committees really struggle to think of their new hire in entirely independent terms — wanting to either replicate or avoid at all costs the characteristics of the incumbent CEO. The board or search committee needs to think only about the organization — its mission and its future — and to find the leader who can most likely bring its future and mission to fruition.

4. Allowing the Philosophical to Conflict With the Practical

The perfect theoretical candidate will always be stronger than the real people God uses to lead organizations. Moreover, do not expect a highly qualified external candidate to know the peculiarities of your organization as well as a possibly less qualified internal candidate.

5. Permitting the Incumbent to Determine His/Her Future Role

The board needs to define what role, if any, the incumbent leader will have in the administration of the new leader. While emeritus titles are honoring, the new CEO should not be hamstrung by a board’s sentimental or even practical commitments to the incumbent.

There is no greater gift to give to a departing leader than to cap his or her tenure with the assurance of the organization’s continued success. And a departing leader’s legacy can only flourish if the succeeding candidate actually succeeds and that must become the sole point of focus for a responsible board in any succession consideration.

This article originally appeared in Evangelicals magazine.

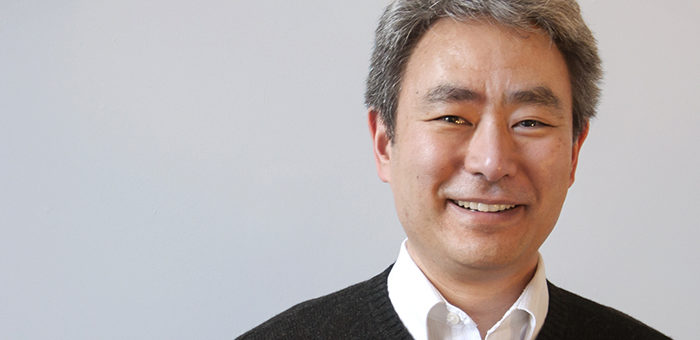

Price Harding is founding partner and chairman of CarterBaldwin Executive Search. Over his 30-year executive search career, he has been principal consultant on more than 1,000 successfully completed recruiting engagements for C-Level leaders, officers and directors for privately held and publicly traded companies. Prior to entering the recruitment industry, he served as director of operations for an equipment manufacturing company. Harding holds a bachelor’s degree in theology from Baptist University of America, and conducted master’s level studies in pastoral counseling at Temple Baptist Seminary in Chattanooga.

View All Articles

View All Articles