L. Roy Taylor serves as stated clerk of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in America. He served as a pastor for 16 years and as an adjunct professor of practical theology at Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson for 10 years. Taylor also acts as the chairman for the board of the National Association of Evangelicals. He earned his M.Div. from Grace Theological Seminary and his D.Min. from Fuller Theological Seminary.

I served as a PCA pastor for 16 years and a seminary professor for 10 years, before coming to my present position as stated clerk of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in America. So I experienced the challenges and frustrations a lot of pastors face financially.

Appropriate Compensation

A lot of ministers consider it unspiritual to negotiate with the search committee concerning their total compensation. I served two churches; in both instances I simply listened to the total package the churches offered and only made suggestions as to the breakdown of the total. According to research from the National Association of Evangelicals with over 4,000 senior pastors, 50 percent make $50,000 or less per year.

Like many pastors I had no training in business and finances. I went to a Christian college for a pre-seminary degree. I attended three theological seminaries. But in well over a decade of higher education, I did not have a single course in financial management. I had to pick it up for myself from family, friends, and my own reading.

In my denomination, a college and seminary degree are usually required for ordination, equivalent to the number of years of education a lawyer would receive. I served churches whose members’ average income was higher than mine. Until our oldest went to college, my wife, Donna, was a stay-at-home mom. Like most parents, my wife and I wanted our children to have similar, though not the same, advantages as their church friends. That was difficult, even with lower expectations.

Retirement Woes

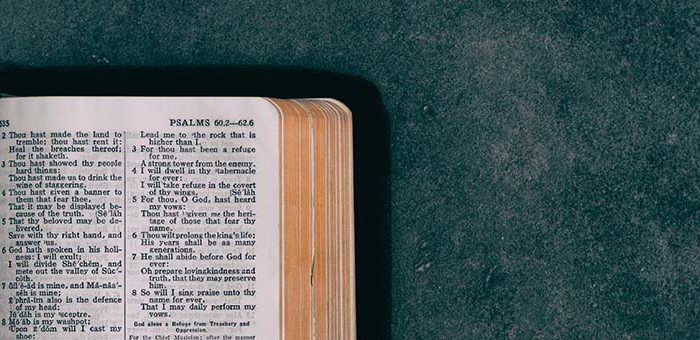

When I began ministry, I had the opportunity to opt out of Social Security. In order to do so I had to sign Form 4361 that “I am conscientiously opposed to, or because of my religious principles … the acceptance … of any public insurance that makes payments in the event of death, disability, old age, or retirement; or that makes payments toward the cost of, or provides services for, medical care.”

My father died when I was three months old, leaving my mother a widow with three small children. My mother received Social Security payments until each child became 18 years old. I could not opt out of Social Security because I simply thought it was a poor investment. I could only opt out on the basis of religious conviction. Therefore, I did not opt out. Now as I approach retirement, I am glad that I did not opt out of Social Security.

In 2010 our denomination’s Retirement Benefits, Incorporated (PCA-RBI) commissioned a survey of PCA ministers and discovered that about one-third had opted out of Social Security and therefore would receive no Social Security benefits, including Medicare. That poses a significant mercy-ministry challenge for our denomination.

RBI is seeking to raise millions of dollars to assist ministers and their families as the ministers retire or die. Though no follow-up survey has been commissioned since 2010, it is hoped that the situation has improved somewhat. PCA-RBI has published “Call Package Guidelines” to assist search committees, sessions (boards of elders) and presbyteries in providing for pastors adequately.

Many Baby Boomers are not financially prepared to retire. Baby Boomer ministers may be less prepared. Though longevity has increased and people are healthier than in previous generations, some pastors are delaying retirement primarily for financial reasons. They cannot afford to retire. Fifty-eight percent of pastors have less than $50,000 set aside for retirement. With more ministers delaying retirement, some ministry opportunities that retiring ministers would have vacated are not available for ministers graduating from seminary.

Some churches have been faced with awkward circumstances in which the pastor needs to retire due to his diminishing abilities and energy for the good of the church, but is unable to do so for financial reasons. The PCA began in 1973 with a shortage of ministers; in 2019 we have more ministers than we have paid ministry positions. Some, though certainly not all, of that surplus is due to ministers’ delaying retirement for financial reasons.

Total Call Package

Defined Benefits Retirement programs are the rare exception rather than the rule in denominations today. Ministers and church staff members are responsible to contribute to their own retirement accounts, though churches and ministries are encouraged to contribute additionally to their ministers’ and church workers’ retirement accounts.

Some churches just provide a “total call package” and expect the pastor to come up with a formula to how to allocate the various items such as salary, housing allowance, state income tax, federal income tax, self-employment tax, medical insurance, and retirement contributions. Many churches do not realize that the portion of the “total call package” the pastor has left on which to support the family is considerably less than the “total call package.”

Medical insurance costs have increased for everyone. Denominational health insurance plans are going out of business due to adverse selection, which makes medical insurance for pastors more difficult to obtain and more expensive. Nearly 60 percent of pastors do not receive any retirement or healthcare benefits from their church.

Seminary Debt

I finished my higher education through to a doctoral degree with no student loan debt whatsoever by working my way through school, my wife working to help, and through benefactors’ support that kept tuition low at the institutions I attended. Up until the late 1960s many denominations did not charge any tuition for their members to attend their seminaries. There were often reduced rates for pre-seminary students in denominational colleges. A few well-endowed seminaries still underwrite a majority of students’ theological educations.

The PCA has assessment centers for potential missionaries, church planters and campus ministers. The assessment process is to determine candidates’ spiritual growth, gifts for specialized ministry, marriage stability, psychological stability, and includes a component on financial debt. Sadly, some otherwise well qualified candidates are turned down due to high indebtedness, particularly student-loan debts. Still, some of those ministers become pastors, as churches do not consider the debt load of a potential pastor when they issue a call.

A law school, dental school or medical school graduate has a reasonable expectation to have sufficient income to pay off his or her student loans within 10 years of graduation. A pastor does not necessarily have that expectation.

Hard Decisions

Recent seminary graduates who are called to small churches face immediate financial challenges paying for the needs of growing families and servicing their student loan debts. The first thing to be omitted is retirement preparation, which may not be regretted for decades. The next is often health insurance, which may be quickly regretted.

Looking back, I wish I as a young man had listened to some wise financial counsel given me. I wish I had made some wiser financial decisions. But I am grateful that I will have the resources to retire from full-time work someday.

With due apologies to John Wesley, who is quoted as saying, “Earn all you can, save all you can, give all you can,” my wife and I have developed our own strategy over five decades of married life: First, don’t live beyond your means. Second, live within your means. Third, learn to live below your means, all while saving and investing wisely and giving to the Lord’s work.

A New Day & New Resources

The long-term solution to pastors’ financial challenges has a number of components for pastors themselves, congregational leaders, denominations, networks, educational institutions, and foundations. An important and essential component of that solution is pastoral training in wise financial management. I am glad that the NAE is taking the initiative to provide online video courses that help pastors with personal and church finances, and through a major grant is able to offer matching funds to several denominations to help their pastors with retirement readiness, student loan repayment and medical assistance grants.

This article originally appeared in Evangelicals magazine.

View All Articles

View All Articles