Secular intellectuals have not been kind to the evangelical mind. They are inclined to see evangelicals as a menace to progress and free thought. Yet their scorn cannot ease a vexing fact: American evangelicals, so maligned as anti-intellectuals, have a habit of taking certain ideas very seriously. True conversion is, of course, a matter of the heart. One cannot cogitate all the way to Jesus. However, if your heart is right with Christ, your head must be in order too. Evangelicals have always understood the sins of modern life as both the misadventures of the unsaved souls and as the fruit of the intellectual error, even as they have disagreed on both the best path to salvation and enlightenment.

Evangelicalism is a far more thoughtful and diverse world than most critics — and even most evangelicals themselves — usually realize. Yet it does host a potent strain of anti-intellectualism, a pattern of hostility and ambivalence towards the standards of tolerance, logic and evidence by which most secular thinkers in the West have agreed to abide. Contrary to the insinuations of many who have chronicled the fortunes of American evangelicals, this anti-intellectualism is not, primarily, due to “a potent and disturbing set of authoritarian tendencies” in conservative evangelical culture (Bible-Carrying Christians: Conservative Protestants and Social Power, 2002). There is no denying that the Bible has tremendous power among evangelicals, or that pastors, activists, and other leaders wield influence over their flocks. However, evangelicals are less like Jesus and more like Jacob. They constantly wrestle with the forces that rule them.

The central source of anti-intellectualism in evangelical life is the antithesis of “authoritarianism.” It is evangelicals’ ongoing crisis of authority — their struggle to reconcile reason with revelation, heart with head, and private piety with the public square — that best explains their anxiety and their animosity toward intellectual life. Thinkers in the democratic West celebrate their freedom of thought but practice a certain kind of unwavering obedience — bowing to the Enlightenment before all other gods — that allows modern intellectual life to function. Evangelicals, by contrast, are torn between sovereign powers that each claim supremacy.

To some degree, this is a universal human problem. All of us, at one time or another, find ourselves tormented by rival pressures and drawn towards incompatible goods. Evangelicals’ theological heritage, however, has aggravated this plight. Their intellectual history is peppered with compromises, sleights of hand, and defensive maneuvers, a combination of pragmatism and idealism that has made evangelicalism one of the most dynamic and powerful phenomena in Christian history, as well as a minefield for independent thought.

This story’s most recent chapter began with the assembly of a small group of evangelical thinkers in the years after World War II. These men sought to banish the stereotype of evangelicals as unschooled rubes and to mold disparate believers into a single evangelical mind. Any consensus they achieved was imaginary, but sometimes fiction is nearly as powerful as truth. Their ideas spurred other thinkers across a spectrum of theological traditions to reconsider the essence of what it meant to be “evangelical” in modern America. Even if no single set of doctrines can neatly summarize evangelicalism, its leaders found themselves circling around a common set of questions that had preoccupied their communities for hundreds of years. They grappled with these dilemmas not in secluded cells cordoned off by creed, but in the same whirl of social change and global upheaval through which all Americans trekked toward the end of the 20th century. Like everyone else, they were looking for firm footing. They craved an intellectual authority that would quiet disagreement and dictate a plan for fixing everything that seemed broken with the world. They did not find it, and are still looking.

Few of the actors in these pages thought of themselves as political activists (though a small number did). We cannot comprehend conservative Protestants, or their place in American culture, solely in terms of “values voting.” We have to take seriously the intellectual traditions — both those peculiar to Christian circles, and those circulating in the broader bazaar of ideas — that have influenced the way evangelicals think about the world. American evangelicals are not just followers of an ancient faith. In recent decades, they have proved themselves to be both the challengers and children of the Cold War age of ideology and the fight to save — or scrap — Western civilization.

These conservative Protestant thinkers and actors are, in part, the creatures of historical circumstances unique to 20th-century America, but they did not first appear crawling out from the primordial muck of the Scopes trial. Their story is part of the American political chronicle and the “culture wars” — but it is inseparable from the larger narrative of Western intellectual history. Their driving questions are the questions that defined the postmedieval age. Evangelicals were, in this sense, among the first moderns. In their attempts to subjugate reason to the rule of faith and personal experience, in some ways they anticipated postmodernity too.

In “Apostles of Reason,” Molly Worthen recasts American evangelicalism as a movement defined by the problem of reconciling head knowledge and heart religion in an increasingly secular America. This excerpt from “Apostles of Reason” © 2013 by Molly Worthen has been edited for purposes of Evangelicals magazine and is used by permission of Oxford University Press. Order at Global.OUP.com/academic.

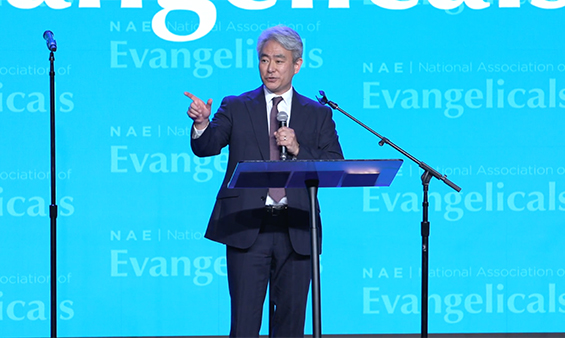

Molly Worthen is assistant professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and author of “Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism,” among other books. She teaches courses in global Christianity, North American religious and intellectual culture, and the history of politics and ideology. Worthen is a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times and has written about religion and politics for the New Yorker, Slate, the American Prospect, Foreign Policy and other publications. She holds a B.A. and Ph.D. from Yale University.

View All Articles

View All Articles