In a recent New York Times article, Molly Worthen asks the question we’ve heard from countless church leaders: “Is there a way to dial down the political hatred?” We seem to have reached a place where the overwhelming majority are burned out by the endless and rapid cycle of outrage, yet completely unsure both of how we arrived at this point and how to dig our way out.

In her analysis, Worthen begins to shed light on the first of these questions by tracing how political identity progressively supplanted a religious one. Thus, old religious dogmas were not dismantled but merely replaced with a political tribalism complete with its own gatekeepers, scapegoats and prophets. While many continue to embrace the culture war, a growing majority are simply exhausted.

Church leaders must recognize that this exhaustion cannot be addressed by simply opting out of cultural engagement. Condemning the culture wars and retreating ignores the challenging reality most Christians face in a rapidly secularizing country. Instead, leaders need to offer a holistic approach to culture that simultaneously addresses concerns of hostility, empowers creativity, and refocuses mission on love and our identity as Christ followers.

In this respect, a good starting point is to conceive of cultural engagement as involving three distinct roles. Just as with a three-legged stool, all three legs are critical to its balance, and the absence or corruption of any one destroys its integrity. The first role is culture creator — those innovative leaders who engage the world by creating a compelling vision of what the world might look like if Christ reigns as king. The second role is cultural missionary — those contextualizing leaders who navigate the complexity of the Christian mission by not only interpreting the world for the Church, but interpreting the Church for the world. The final role, and perhaps the most popular and misunderstood, is the culture defender. Through articulating a clear and compelling vision of Christian orthodoxy, the role of the defender combats the forces of syncretism and theological drift. This extends beyond debate within the Church as defenders serve a critical function in advocating for the rights of Christians to maintain beliefs that may become, and in fact are now becoming, culturally untenable.

Our current exhaustion arises when this role of cultural defender becomes not only dominant but exclusive. As defense of the gospel and the Church has transitioned to a war for the gospel and the Church over culture, we not only lose sight of the other two elements of cultural engagement, we risk losing sight of the entire purpose in engaging: God’s mission to show and share the love of Jesus.

Cultural Divide Among Christians

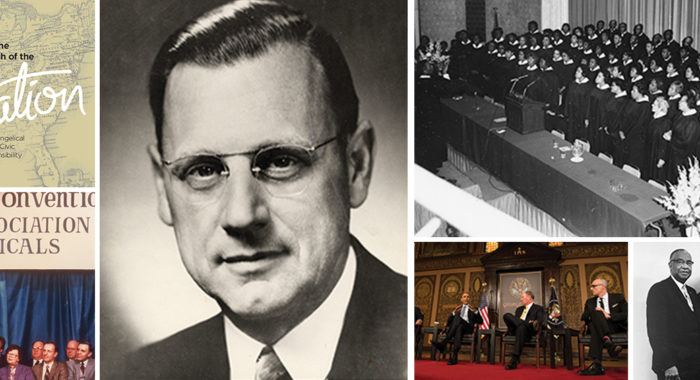

The conflict that can arise when culture defenders dominate our mission of cultural engagement is illustrated in a rarely remembered, 1995 exchange between church historian John Woodbridge and Focus on the Family President James Dobson. In Christianity Today’s “Culture War Casualties,” Woodbridge cautioned against the growth of warfare rhetoric among evangelicals. In his perspective, this rhetoric fed polarization by diminishing nuance and empowering extremist voices. While recognizing culture’s increasing hostility to faith, Woodbridge called evangelicals to consider how the culture war was shaping their witness. Although it demanded sacrifice, it was possible to love your cultural enemies and defend the faith.

Singling out Dobson by name, Woodbridge charged that the evangelical leader’s frequent reference to a “civil war” of values in popular media was a significant factor in its embrace by the broader movement. Dobson later responded in Christianity Today, arguing warfare language was scriptural, and that Woodbridge and other evangelicals had lost the forest among the trees. “Instead of decrying the evils around us,” Dobson lamented, they “conclude the real problem is one of inappropriate language used by alarmed Christians.” Frustrated at the perceived apathy of his fellow evangelicals, Dobson asked those “on the sidelines” of the culture war to refrain from making the task of waging it any more difficult.

Woodbridge responded by agreeing that a cultural hostility to orthodox Christianity was an urgent and daunting challenge but maintained that “war talk” was corrosive in the long-term to Christian witness. By defining victory in political terms, warfare rhetoric fostered fear of those outside the Church, the very people the gospel calls us to love. Woodbridge concluded that while this call to war could invigorate Christians in the short run, it eroded the foundations of society by engendering fear of our neighbors.

Generational Evangelical Tensions

While few remember the exchange, it produced waves of letters to the point that CT’s editors needed to step in. In their respective positions, Dobson and Woodbridge captured a defining tension within evangelicalism between engagement as war versus mission. For those who felt embattled by modern culture, Dobson captured their anxieties over new cultural moralities and frustrations at a perceived anemic pushback from others in the Church. As they felt mounting pressure to conform to an emerging secular ethic, the lesson they drew was to fight harder and, at times, to turn to politicians who promise to fight for while not necessarily with them.

On the opposite end, Woodbridge embodied those concerned over the growing obsession with conflict, recognizing the damaging impact it can and has had on our witness to our neighbors. While concerned about the same social pressures, they recognized how culture wars have exacerbated the situation for evangelicals in public. This feeling of being caught between their evangelical family and their mission field inevitably alienated them from both, aggravating exhaustion.

In recent years these two positions have only intensified. Where their shared theology provided the illusion of unity, fundamental differences on engaging culture are proving increasingly difficult to bridge. Often couched in eschatological terms, the primary lens of engagement for culture defenders was conflict against an opposing world. In contrast, culture missionaries located the mission of God as one of renewing the world. As such, our cultural engagement revolved around showing and sharing the love of Jesus to a

lost world.

What Identity Are We Defending?

As we look for ways to put the three-legged stool back together, the answer lies in resisting the opposite temptations in a healthy vision of cultural defense. We are firmly within a post-Christian world, and hostility to orthodox Christianity presents real challenges. When church leaders dismiss these concerns, it can push Christians into the arms of those who foster conflict. If an “evangelical” identity is going to be anything more than a political identity, we must contend for a theological identity that takes orthodoxy seriously and presents it in creative ways that emphasize what we are for, rather than what we are against. We must do so without reducing cultural engagement to its caustic or isolationist tendencies, but to care about — and even defend — orthodoxy and proper culture engagement.

Central to an evangelical theological identity is rethinking what we are defending. For generations, political and culture wars have set the table to the point that even words like “heretic” are ripped from their theological meaning and used as weapons in a political conflict. Within this culture, too many evangelicals have had their orthodoxy questioned simply because they challenged political idols.

Turning to true defense of a gospel identity, our emphasis must be both theological and generational. Whatever success the evangelical church has experienced in past generations lies less in its loudest voices than in its quieter, more obscure leaders. Returning to the example of John Woodbridge, few have defended the evangelical doctrine of inerrancy so successfully. His career proves the Church’s need for leaders who will thoughtfully defend its beliefs against waves of derision and mischaracterization of this world.

Yet just as important has been Woodbridge’s dedication in passing this theological heritage to generations of evangelicals through teaching and writing. Time consuming, humbling and not for the faint of heart, the challenge of defending the gospel in our communities, churches and seminaries often goes unnoticed and underappreciated. Feeding the sheep, it may not look like winning to the outside but seen within a kingdom lens, its value is eternal. Indeed, if there are any winners in the evangelical movement, it is its pastors, seminary professors, Sunday school teachers and next-door neighbors — all who are faithfully engaging their communities with little fanfare.

We feel the exhaustion. We are exhausted by the same debates and tribalism that ensnared past generations. So as church leaders consider what it means to engage a culture that is increasingly hostile, we need a holistic approach that simultaneously defends, creates and contextualizes.

We will need all the legs of the stool not to fall — and the stool is wobbling right now. Our posture will shape our future path, and important conversations are before us. May we wisely engage this moment, so that future generations see an evangelicalism that reflects the character of Christ and the teachings of Scripture in the fullness of the Spirit.

Ed Stetzer is a professor and dean at Wheaton College where he also serves as executive director of the Wheaton College Billy Graham Center. He has planted, revitalized and pastored churches; trained pastors and church planters on six continents; and written hundreds of articles and a dozen books. He previously served as executive director of LifeWay Research and vice president of the LifeWay Insights division. He holds two master’s degrees and two doctorates, a D.Min. from Samford University and a Ph.D. from The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.

Andrew MacDonald is the associate director of the Billy Graham Center Institute and also serves on team of The Exchange, a platform to discuss how Christians can engage culture well. He has served as an adjunct professor at numerous institutions. MacDonald is currently a Ph.D. Candidate in historical theology at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. He earned his M.A. in philosophy of religion and ethics from Talbot School of Theology.

View All Articles

View All Articles