Evangelicals have been taking some hard hits lately. Some are even abandoning the label because it has become too associated with a political agenda. As a historian who has written and thought deeply about the relationship between evangelical Christianity and American life, I am fully aware that for every positive contribution evangelicalism has made to American culture, we can point to another way in which evangelicalism, sadly, has been at the forefront of some of the nation’s darkest moments.

It is imperative that evangelicals study their past and come to terms with it. This requires us to lament the moments in which we have failed and celebrate the moments when the good news of the gospel has changed lives, set people on a course for eternity with God, and led them to act in ways that are good and just. Throughout history, evangelicals have contributed to society in positive ways when we have emphasized hope over fear and humility over the pursuit of power.

People of Christian hope know that a Promised Land awaits them, but while they are here — as aliens and strangers — they devote themselves to the work of justice. One day God’s kingdom will come, and all will be made right. In the meantime, we are called to the work of preparing for it. Such kingdom-building obedience has always had benevolent consequences for society.

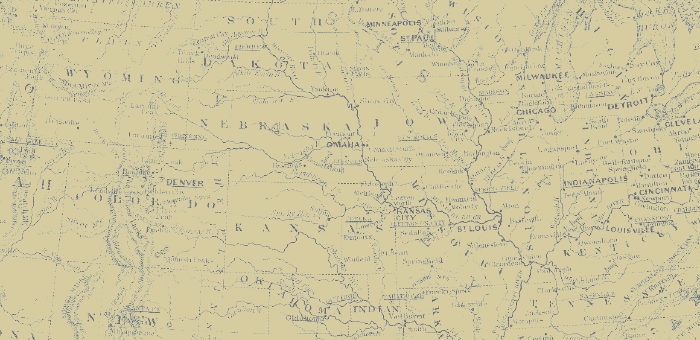

For example, during the 19th century, tens of thousands of Americans found hope through the evangelical revivals sweeping the nation known as the “Second Great Awakening.” Those touched by the Holy Spirit practiced their newfound evangelical zeal by addressing a host of social problems undermining the moral fabric of American society.

Evangelical reformers fought for the dignity of women. They were at the forefront of efforts to end slavery. They mobilized churches to aid the poor and the oppressed. Sarah and Angelina Grimke, Arthur and Lewis Tappan, Sojourner Truth, Charles Finney, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Harriet Beecher Stowe all employed evangelical conviction in the service of social justice.

The legacy of the Second Great Awakening’s hopeful kingdom-builders has been long. The Salvation Army, the Women’s Christian Temperance Movement, the movement to provide common schools for women and the poor, Pacific Garden Mission, Prison Fellowship, Christian Community Development Association, and Samaritan’s Purse, all find their roots in one of the nation’s most important evangelical revivals.

Evangelicals have also made a positive impact on this world when they have modeled their lives after a Savior who relinquished worldly power — even to the point of giving his life. Evangelical humility is always centered on the cross of Jesus Christ, a self-sacrificial act that ushered in a new kind of political entity — the kingdom of God.

Millions of evangelical Christians around the world have humbly served their neighbors and made a positive impact on the world. Most of them are not famous or ambitious by the standards of this world.

For example, the first century Christian church flourished when ordinary believers were willing to face death for the cause of Christ. The early church lived a countercultural faith in the Roman Empire by identifying themselves with the poor.

In a fascinating award-winning article in The American Political Science Review, political scientist Robert D. Woodberry argues that evangelical missionaries, especially those serving in places where Christians have been persecuted, have “heavily influenced the rise and spread of stable democracies around the world.” They have been “a crucial catalyst initiating the development and spread of religious liberty, mass education, mass printing, newspapers, voluntary organizations, and colonial reforms, thereby creating the conditions that make stable democracy more likely.”

The 21st century United States presents a host of new challenges for evangelicals. If we are going to place hope over fear, and humility over power, we will need to do less preaching and more listening. We will need to have conversations, not arguments. We will need to learn to engage in dialogue that respects the dignity of all of God’s human creation and not cast our enemies into perdition. We must also be prepared for the possibility of exile and perhaps even suffering. Whatever the future holds for American evangelicals, the act of remembering our past can help us to move forward in hope and humble service.

This article originally appeared in Evangelicals magazine.

John Fea is professor of American history and chair of the history department at Messiah College in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania. He is the author or editor of six books, including “Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump,” and his essays and reviews have appeared in a variety of scholarly and popular venues. Fea is a recognized expert on the historical influence of evangelicalism in American culture. He holds an M.A. in church history from Trinity International University and a Ph.D. in American history from Stony Brook University.

View All Articles

View All Articles