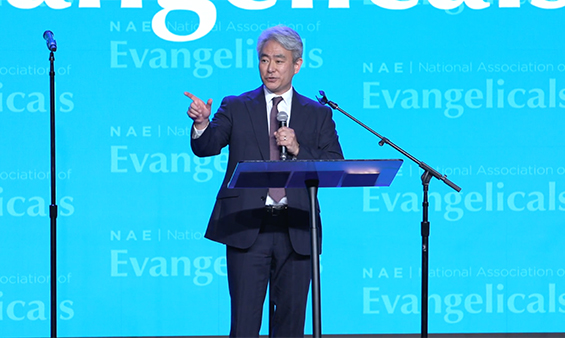

Everyone wants to know what evangelicals think — particularly in the election season. But who are researchers talking about when they refer to evangelicals? In Today’s Conversation with Leith Anderson, Ed Stetzer talks about the challenges and opportunities in defining and researching evangelicals.

In this podcast, you’ll hear insight from a leading Christian researcher on:

- The different ways researchers identify evangelicals;

- How to define evangelicals by their beliefs;

- The statistical realities of how evangelicals vote; and

- What the future looks like for evangelicalism in the United States.

Read a Portion of the Transcript

Leith: You are a professional researcher and know this extremely well. Why is this important to clarify this definition of evangelicals?

Ed: Well, I think the reality is that you can look at this definition in multiple ways. You could come at this from, there’s a thing called the RELTRAD, which is a tool that sits on top of the General Social Survey that actually uses what you belong to. You fill out a form, you say that you’re PCA, or Assemblies of God, Presbyterian Church in America, you will be counted as evangelicals. So that’s by belonging. We think that’s helpful. And there’s another by self-identification, this is what Pew does. So Pew identifies you as evangelical if you say that you are an evangelical or you are born again, and so that’s how Pew uses that. What we’re trying to do here in this project – two years we’ve worked together with the NAE and with LifeWay Research – is to really look at it from a perspective of beliefs. Too often it get’s categorized – particularly in political season – by politics, or it gets categorized by some other factor. So by looking at beliefs we can let people and what they believe place them in the evangelical bucket for research. And it gives us another tool, another helpful tool – and I would say a better tool – than simply saying, “Well, they attend this church. They might not have evangelical beliefs. Or they might attend a church that has non-evangelical beliefs but they themselves are evangelical.” So this gives us that tool. And I think it will be widely received to help people to use this for researchers and analysts to say,“Alright, who are evangelicals?” – particularly because it’s the NAE LifeWay research definition of evangelical belief. And in doing so, it sort of helps define for researchers what the most well-known association of evangelicals thinks defines the belief of the movement statistically.

Leith: So evangelicals actually get to define who are evangelicals, instead of somebody externally doing it for us.

Ed: Which would be I think a helpful thing. Considering that sometimes when you read things – you know, in the media or elsewhere – people don’t know the difference between an evangelical or five other things. So I think getting a key read from a key organization with a statistically validated process will really help answer some of these questions.

Leith: I’d like you to talk about what the method has been for the NAE LifeWay process. And I’ve got to put this in here, you know all the technical language, so you need to say this in terms that I and others will understand. Explain how you do this. What’s the process through which you go?

Ed: What you try to ask is: Are there certain questions that you can ask that people who hold evangelical beliefs will answer, and people who don’t hold evangelical beliefs will answer differently. And so that’s what we sought to determine. Even before we did that, we went through and we started with some theologians. And we asked the theologians to help us come up with some questions. And so these theologians worked with Ron Sellers and Grey Matter Research and came up with a series of questions. When we kind of started the conversation, we wanted to broaden beyond a smaller group of theologians and have a more diverse group of sociologists and evangelical leaders and theologians of different races, different ethnicities, different backgrounds. So we asked sociologists, for example: What do you think about this methodology approach? We removed certain kinds of questions — things that were what we called double-barreled — that asked, “Do you think Jesus is the only way and that you should share the good news?” That’s a double question, rather than: “Do you believe that Jesus is the only way?” That’s some feedback we got from sociologists and researchers that we consulted with like Nancy Ammerman and Christian Smith of Notre Dame and others. So then we went by and came up with 17 questions that we then began to test. We were looking to see if they were able to scale out — or factor out, I should say — certain groups and keep in others. So we tested those questions on one occasion, and we came back again and did another series of tests on those, ran them by the group of evangelical leaders and theologians, and back to our original group of theologians and evangelical leaders. And so what we want to end up with — and what we ended up with — is something that ultimately three in 10 Americans sort of fit the definition, and it’ll shape other ways depending on how people ask the question. But specifically looking at this kind of statistically validated methodology that isn’t just four questions we came up with, but four questions that we tested. And there are certain relationships between the questions that are worth noting about correlation and elsewhere, but you told me not to get too technical, and I won’t. But at its simplest: It works statistically; It works theologically, according to the theologians and the NAE. And when those two things come together, we have a good tool and helpful questions.

View All Podcasts

View All Podcasts