The telephone is a marvelous invention. It allows us to reach out and touch friends and family across the miles. As a child I grew up overseas and attended boarding schools in a time when telephones were unavailable. I sometimes felt like I was in prison – though having since seen a number of real prisons I now realize that my complaints were overblown. But I was certainly cut off from my family with little communication for months at a time. Despite the fact that I had, and still have, loving parents, the deprivation of regular contact with my family profoundly impacted my development.

Persons who are incarcerated face severe constraints on their mobility, communications and potential for developing healthy relationships. In part, this is by design: Prison is a form of punishment, and is meant to be a deterrent to unlawful behavior. But being sentenced to serve time behind bars does not erase the human dignity that derives from our common birthright as persons who bear the divine image. Nor does a prison sentence cancel the fact that human beings are created by God to live in relationship with others. No one is, or can be, an island.

Further, since the vast majority of prisoners will eventually be released to rebuild their lives as neighbors in our communities, co-workers in our businesses, and members of our families and churches, we have a vested interest to make their time behind bars as rehabilitative as possible. If we want prisoners to return to our communities as productive, contributing members of society, we should make sure that they have an opportunity to develop and nurture positive relationships even while they are locked up.

But for many prisoners, the opportunities for maintaining supportive relationships with those outside the prison walls are few and far between. Prisons are often located far from population centers where most families and friends live. Prison siting decisions are often not made with rehabilitation in mind. Depressed rural communities seek new prisons as a source of employment. Wealthier communities reject prisons, fearing insecurity and stigma. But even when there are prisons available near an offender’s home and family, prisoners are not always incarcerated there. Whether for reasons of cost, bureaucracy, or vindictiveness, prisoners are often held in facilities so far from their homes, and inaccessible by public transportation, as to make regular visits impractical if not impossible.

Many prison administrators also impose heavy burdens and restrictions on prison visitors. The need for security checks is understandable. But limits on visiting days and hours, barriers to physical contact, lack of privacy, and many other factors complicate prison visits for both family and volunteers.

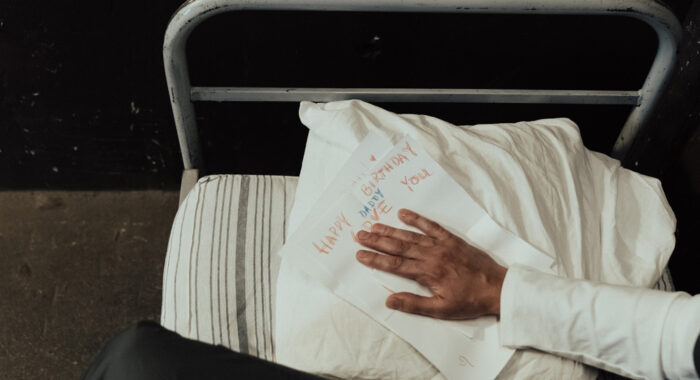

In these cases regular telephone calls are the next best thing. The telephone offers a lifeline when physical visits are impossible. It enables prisoners to keep in touch with their spouses, children and parents. This can be an important source of encouragement to children of the incarcerated: Even a long distance parent is better than none.

Maintaining prisoners’ ties with their families, as well as with volunteers from the outside who engage in prison visitation ministries, is key to rehabilitating offenders and preventing recidivism. The Bible tells us that “it is not good for man to be alone.” Marriage and family are fundamental building blocks for society. Human beings are created in the image of the triune God: Father, Son and Holy Spirit, who exist in eternal community. Human beings share in this essentially social nature. It is cruel and unusual punishment to deprive prisoners of regular contact with their families. It is particularly crucial for those families who cannot physically reach out and touch their loved ones who are incarcerated, often far from home.

Christian concern for connecting with those behind bars goes even beyond blood ties. Christians are followers of Jesus, who expressed a special concern for the welfare of prisoners, and who identified with prisoners in his unjust arrest, trial and execution. Toward the end of his life, Jesus talked with his followers about the final judgment, a time when both people and nations will be accountable to God for their actions. Jesus’ words, recorded in Matthew 25, tell us that people and nations will be evaluated according to how they have treated their most vulnerable neighbors, those he called the “least of these, my brothers and sisters”: whether they have fed the hungry, clothed the naked, cared for the sick – and, whether they have visited those in prison. Jesus said that when his followers care for the vulnerable, we are actually caring for Jesus himself.

Christians do not believe that our actions, however noble, can earn our salvation. The Bible is clear that all human beings are sinners and, apart from God’s grace given through Jesus Christ, are incapable of reaching their God-given potential. But Jesus indicates that those who become his followers will demonstrate the authenticity of their faith by their actions.

In Jesus’ day, the telephone had not been invented. The only way to visit someone in prison was to go there in person. And that is still the gold standard in prison ministry. But when a personal visit is impossible, the telephone at least offers the opportunity for live interaction that a letter does not provide. It is a way to fulfill Jesus’ mandate that we visit those who are in prison.

For these reasons, prison administrators should do everything possible to facilitate prisoner access to regular telephone calls that are affordable to their families. Telecommunications technology now allows most people to talk to friends and family anywhere in the world for only pennies per minute. There is no justification for burdening prisoners’ families with uncompetitive phone rates. These families already face the burden of having lost a breadwinner, and in most cases are among the poorest households in our communities.

If public appropriations in an era of tight budgets are inadequate to fund our current prison system, we should look for ways to reduce the prison population through more effective crime prevention, through sentencing reform that makes better use of alternatives to incarceration, and through prison reforms that lower recidivism rates – including bringing an end to exploitative prison telephone rates.

Galen Carey, NAE vice president of government relations, is responsible for representing the NAE before Congress, the White House and the courts. He works to advance the approach and principles of the NAE document, “For the Health of the Nation.” He is also co-author with Leith Anderson of “Faith in the Voting Booth.” Before joining the NAE staff, Carey was a longtime employee of World Relief, the relief and development arm of the NAE, serving in Croatia, Mozambique, Kenya, Indonesia and Burundi. He received an M.Div. from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, and a Doctor of Ministry from McCormick Theological Seminary.

View All Articles

View All Articles