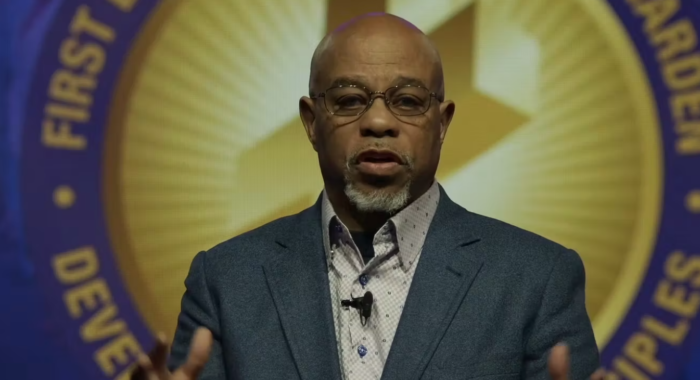

A.G. Miller is associate professor of religion and Africana studies at Oberlin College and pastor of Oberlin House of the Lord Fellowship in Oberlin, Ohio. Miller has served in various ministry capacities in churches and nonprofits. He authored “Elevating the Race: Theophilus G. Steward, Black Theology, and the Making of an African-American Civil Society, 1865-1924” and the upcoming book “Fundamentally Black: The Rise of Evangelicalism on the African-American Community.” He has taught at Oberlin College since 1991. Miller holds degrees from Adelphi University and Princeton University.

With the election of President Barack Obama in 2008, many claimed we were entering an era of a post-racial, multi-ethnic society. Events after the president’s election have tempered this sentiment. This country has a complicated relationship to race and ethnicity, and this is especially true for black and white relationships and for Christianity in America.

As an African American religious historian and pastor of a predominately black Pentecostal church, I offer a few examples that highlight the problem and promise for race in American churches and denominations, specifically addressing black and white history.

Conflicted on Slavery

During our nation’s early colonial period, the First Great Awakening propelled evangelical Christianity — sweeping across the colonies, converting white, black, free and slave, and expanding the Methodist, Baptist and Presbyterian denominations.

The colonies and the early republic were conflicted on slavery as many saw it as a “sin.” Both Baptist and Methodist denominations restricted its leadership from owning slaves. These restrictions had various reactions in the North and the South. Even so, congregations saw blacks and whites worshipping together, albeit on segregated terms, in both the North and South.

A seminal event at St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1787 was more or less replicated among many churches and denominations. St. George’s allowed black slaves and free white people to worship together, but from the position of white supremacy. White people sat in the front seats and were served communion first. When membership overflowed, black people were obligated to give their seats to whites. Black people could minister to blacks, but rarely did blacks minister to whites.

When a new balcony was built at St. George’s, the black community assumed it was built for their usage, and they also contributed financially to its construction. On the day of the balcony’s dedication, the church was packed, and blacks headed to the balcony. But they were abruptly asked to make way for white parishioners. Absalom Jones and Richard Allen led a small group of black members out of St. George’s, never to worship there again.

Separated by Race

Later Jones became the first black priest in the Episcopal Church and founded St. Thomas African Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. Allen stayed within the Methodist Episcopal Church for another three decades and organized a separate black congregation, Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Twenty years of battle with the white Methodist leadership over the operational control of Bethel led to a state Supreme Court case. The court sided with the Bethel congregation in 1816. Other black Methodist congregations joined Allen in celebrating the victory and created a new denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Other Methodist, Baptist, Episcopal and Presbyterian congregations evolved in a similar segregated and separated fashion.

As slavery lessened its grip in the northern states and entrenched itself in the southern ones, the sentiment towards slavery shifted in the southern states to a “necessary evil.” Many black and white abolitionists emerged in the early 1820-30s to put pressure on the slavery system — challenging it on biblical grounds.

Many Southerners pushed back with justifications for slavery from their interpretation of the Bible, pushing some radical abolitionist anarchists to reject the validity of the Bible as the word of God. Many slaves escaped to the North and plotted rebellions — much of it justified on a biblical reading of the God of justice.

After the Nat Turner rebellion in Virginia in 1831, slavery solidified itself as a southern way of life. Those who justified it declared that slavery was “ordained by God.” The three major 19th century evangelical denominations split over the issue of slavery: Methodists in 1844, Baptists in 1845 and Presbyterians in 1861, on the eve of the Civil War.

After the Civil War and the passage of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution, the Southern Methodists created the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church in 1870 to stop its newly freed slaves from shifting allegiances to northern black and white Methodist denominations.

Azusa Street Revival

In the early 20th century, the Pentecostal movement provided a fount of interracial cooperation, even during the racially segregated Jim Crow America. The Azusa Street Revival (1906-1909) in Los Angeles, widely known as the catalyst for the worldwide Pentecostal movement and denominations, broke all racial norms with Russian, Chinese, Mexican, black, and white Southerners worshiping together. Azusa was also hailed for the multiracial leadership of the Apostolic Faith Movement (AFM), led by William Seymour, an African American preacher.

Unfortunately, unclear internal conflicts arose within the AFM by 1909, and it split along black and white racial lines — one branch led by whites moved to Portland, Oregon, and Seymour’s branch remained in Los Angeles. After the split, Seymour restricted the leadership to blacks only.

By the middle of the 20th century, most of the major Pentecostal denominations were organized along racial lines. As white Pentecostal denominations grew in numbers and social stature in middle 20th century America, they organized into the Pentecostal Fellowship of North America (PFNA) in 1948, following the formation of the National Association of Evangelicals in 1942. Among the excluded black Pentecostal bodies was the Church of God in Christ (COGIC), the largest black Pentecostal body in the United States.

Memphis Miracle

Forty years later, conversations working toward reconciliation emerged between PFNA and COGIC. After several years of meetings and dialogues, in 1994, the PFNA leadership disbanded its organization and started the Pentecostal and Charismatic Churches of North America (PCCNA) that was inclusive of black Pentecostal denominations.

This was dubbed the “Memphis Miracle” in part due to the spontaneous foot washing of COGIC Bishop Ithiel Clemmons by Assemblies of God Minister Donald Evans who asked for forgiveness for the racial sins of whites within the Pentecostal movement. This event led to significant conversations throughout the Assemblies of God denomination on the issue of racism.

Still Divided

Events like these are a healing balm for some of the pain experienced among racial lines in our shared history. Still, black and white Christians are divided today.

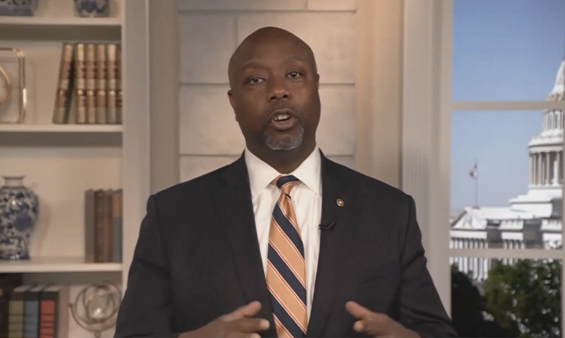

The Pew Research Center found that 68 percent of white evangelicals identify as Republican, while 82 percent of black Protestants identify as Democratic. This highlights differences on political issues, but it is also reflective of a wider range of differing opinions that impact daily decisions, including our worship choices.

There is much to be done within and among denominations, organizations, churches and individuals to bring together the diverse body of Christ, where there is neither slave nor free, black nor white, Hispanic nor Asian. May our coming story bring the God of all races and ethnicities great glory.

This article originally appeared in Evangelicals magazine.

View All Articles

View All Articles