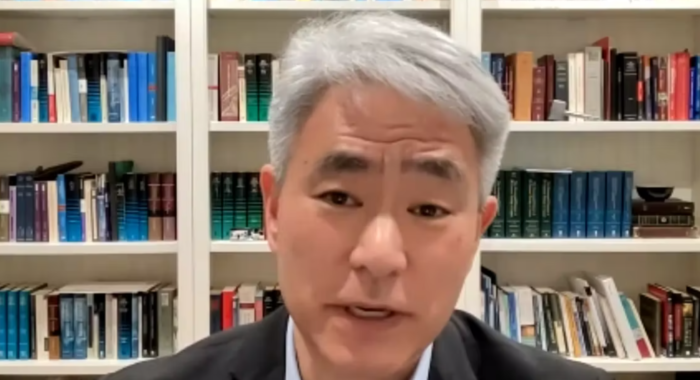

Richard Mouw is professor of faith and public life and president emeritus of Fuller Theological Seminary. He served as the seminary’s president for 20 years. Prior to teaching and leadership at Fuller, he taught at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan, for 17 years. He has participated on many councils and boards, recently serving as president of the Association of Theological Schools. Mouw has written 19 books, including “Uncommon Decency: Christian Civility in an Uncivil World.”

In the 1960s and 70s some of us began calling for a commitment to “evangelical social concerns.” The emphasis was on “getting involved” and “speaking out.” God cares deeply about the issues of public life, we argued. It isn’t enough for us simply to be good citizens by paying our taxes, voting, praying for our leaders and supporting our military. We need to be actively engaged in the public square, guided by God’s revealed standards for the collective patterns of our lives together as human beings.

These days there is little need to make that case. Evangelicals are active in the public square — even notoriously so. But we have not engaged in our activism in a manner that has endeared us to others. Some polls show that even our own younger generation of evangelicals see the white evangelical movement as “mean-spirited” and “judgmental” on issues being debated in the larger society.

If even a subgroup of evangelicalism is contributing to the widespread incivility of our society, what would it take for us to become a part of the remedy? How can we be a more civil presence in North American life?

When I first started writing and speaking on the subject of civility, I was inspired by a wonderful line in a short book by the well-known Lutheran historian and social commentator Martin Marty. Many people who are civil these days, he said, don’t have strong convictions; and many people with strong convictions aren’t very civil. What we need, said Marty, is people with convicted civility.

The Apostle Peter addresses the need for this combination in his first epistle. After telling us to “always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give a reason for the hope that you have,” he immediately adds: “But do this with gentleness and respect.”

This takes spiritual work, cultivating a heartfelt love for our non-Christian fellow citizens with whom we disagree on important matters. But the work must begin with a recognition of what God has done for us in Jesus Christ. “How deep the Father’s love for us” — Christ came to save us while we were still sinners, living in rebellion against the living God. Our civility must be inspired by the more-than-civil love that saves the likes of us!

This article originally appeared in Evangelicals magazine.

View All Articles

View All Articles