Last year, The Atlantic’s Adam Serwer warned of “the false promise of civility” in an article entitled, “Civility is Overrated.” He has a point. Civility, by itself, does not change hearts and minds. And it doesn’t restore the social fabric or establish justice among the nations. Indeed, as Serwer noted, civility is sometimes invoked by evildoers to mask their transgressions or temper their critics.

Take the political demagogue who shakes all the right hands, the church pastor whose outward charms mask inner demons, the neighborly churchgoer whom Martin Luther King famously labeled the “white moderate.” Too often, civility is a ploy by the powerful to defend an unhealthy or unjust status quo. American evangelicalism is not immune from this danger, especially when Western civility norms are claimed as gospel imperatives.

And yet I still think Christians are called to something like civility. Not compromise, passiveness or capitulation. Not niceness, likeability or even winsomeness. The civility to which Christians are called is something closer to the costly engagement that Scripture counsels us to pursue with other image-bearers.

This kind of engagement is what Tim Keller and I advocate for in our book, “Uncommon Ground: Living Faithfully in a World of Difference.” With 10 friends who contributed essays — artists, pastors, scholars and ministry leaders — we explore how Christians can engage with others who have deep and irresolvable differences over the things that matter most.

Humility, Patience and Tolerance

We believe the answer starts with the embodied practices of humility, patience and tolerance. These practices are fully consonant with a gospel witness in a deeply divided age. In fact, they not only make space for the gospel but also point, respectively, to the three Christian virtues of faith, hope and love.

The first of these practices, humility, recognizes that in a world of deep differences about fundamental issues, Christians and non-Christians alike are not always able to prove why they are right and others are wrong. Christians are able to exercise humility in public life because we recognize the limits of human reason, including our own, and because we know we have been saved by faith, not by our moral actions or goodness. That confident faith anchors our relationship with God, but it does not supply unwavering certainty in all matters.

Patience encourages listening, understanding and empathy. Patience with others may not always bridge ideological distance; we are unlikely to find agreement on all of the difficult issues that divide us. But careful listening, sympathetic understanding and thoughtful questioning can help us draw closer to others as we come to recognize the shared experiences that unite us and the different experiences that divide us. We can find common ground even when we don’t agree on the common good. Christians can be patient with others, because we place our hope in a story whose end is already known.

Tolerance is a practical enduring of beliefs and practices that we do not share. It does not mean accepting those beliefs or approving of those practices. In fact, the demand for acceptance is a philosophical impossibility. Every one of us holds views about important matters that others find clearly misguided. There is no way that anyone can embrace all the differing and mutually incompatible beliefs in society today. But we can do the hard work of distinguishing people from ideas, of pursuing relationships with people created in God’s image while recognizing that we will not approve of all their beliefs or actions. Christians can demonstrate tolerance for others because our love of neighbor flows from our love of God, and our love of God is grounded in the truth of the gospel.

All three of these practices — humility, patience and tolerance — encounter stiff resistance in an era of sound bites and echo chambers, where news channels and social media personalities trade nuance for popularity. Too often, Christians are caught up in these very same currents. But if our culture cannot form people who can speak with both conviction and empathy across deep differences, then it becomes even more important for the Church to use its theological and spiritual resources to produce such people. Let us be shaped and reshaped into people whose every thought and action is characterized by faith, hope and love — and who then speak and act in the world with humility, patience and tolerance.

From Tolerance to Love

In fact, when we are motivated by the love of Christ, we can do far more than simply tolerate. Think about your relationships with friends who hold beliefs different from your own. You don’t just tolerate them. You laugh, cry, celebrate and mourn with them. You risk a kind of personal vulnerability that requires more than just coexisting together in the same space. And what about those who overtly reject you or even show hostility to you? The answer is the same. Jesus doesn’t tell us to tolerate our enemies. He says to love them. And thank God that Jesus does not merely tolerate us — he embraces us across the greatest difference of all.

Christians should be leading the way toward engaging with others across difference, because we are called to embody the love that Jesus has shown to us. We should do so with confident hope rather than stifling anxiety, regardless of the political and cultural context that we confront. We should risk entering uncertain and messy spaces. We should risk connecting with others in more tangible and more vulnerable ways, beginning with ordinary acts like sharing a meal or simply having a conversation.

Some people may cast aspersions on us for the company we keep or the places we go. They did that to Jesus, too. And Jesus engaged the world, not just at the possible risk of his comfort or reputation but at the sure and certain cost of his life.

“He has gone to be the guest of one who is a sinner,” they murmured threateningly when Jesus went to the house of Zacchaeus (Luke 19:7), but he still went. “Jews do not share things in common with Samaritans,” the apostle John underscored in Jesus’ encounter with the Samaritan woman (John 4:9), but Jesus still spoke to the woman at the well. “Today you will be with me in Paradise,” Jesus told the thief on the cross (Luke 23:43), and then he died. Through our confidence in the gospel and in the Author and Perfecter of our faith, we seek to live as Jesus lived in a world of difference.

This article originally appeared in Evangelicals magazine. In Today’s Conversation podcast, John Inazu shares more about how to survive and thrive across deep difference.

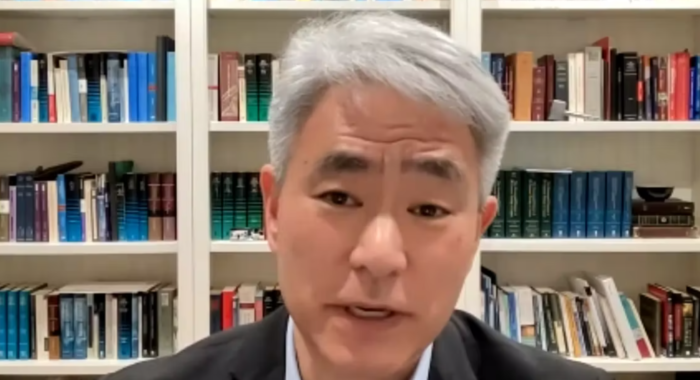

John Inazu is the Sally D. Danforth Distinguished Professor of Law and Religion at Washington University in St. Louis. His scholarship focuses on the First Amendment freedoms of speech, assembly, and religion, and related questions of legal and political theory. He is also the executive director of The Carver Project, a ministry empowering Christian faculty and students to serve and connect university, church and society. He is the author of “Liberty’s Refuge” and “Confident Pluralism” and co-editor (with Tim Keller) of “Uncommon Ground.” Inazu holds a B.S.E. and J.D. from Duke University and a Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

View All Articles

View All Articles