The observation of a veteran missiologist has influenced my life and perspective. He told me that “When the revolutionary guerrillas have lined up Christians for a firing squad out in the jungle, no one is discussing mode of baptism.”

The point is simple: Crisis focuses us on what is most important and brings us together. But there is a subpoint to this lesson as well. When life is easier and freedom abounds, we can easily drift into the luxuries of differences, criticism, separation, divisiveness and isolation. The linear firing squad of the enemy turns into a circular firing squad of friendly fire.

There is an often-overlooked recognition that opportunity should be a louder call to solidarity and cooperation than adversity. We should be focused on the unity of our message instead of the differences of our traditions even when the revolutionary guerrillas are putting down their rifles and listening to the gospel.

What Happened in Jerusalem

The divisive controversies that led to the historic Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15) set the precedent for evangelizing the Roman Empire. The first century church learned early that what happens in Jerusalem doesn’t stay in Jerusalem.

Some men came down from Judea to Antioch and were teaching the brothers: “Unless you are circumcised, according to the custom taught by Moses, you cannot be saved.” This brought Paul and Barnabas into sharp dispute and debate with them. So Paul and Barnabas were appointed, along with some other believers, to go up to Jerusalem to see the apostles and elders about this question. The church sent them on their way, and as they traveled through Phoenicia and Samaria, they told how the Gentiles had been converted. This news made all the brothers very glad. When they came to Jerusalem, they were welcomed by the church and the apostles and elders, to whom they reported everything God had done through them. (Acts 15:1-4)

The two sides were as polarized as political parties in an election year. The traditionalists based their conviction about the necessity of circumcision on the authority of Scripture as taught by Moses. It must have seemed impossible to them that any sincere believer would go against the Old Testament law. They considered this an essential gospel doctrine — without circumcision “you cannot be saved.”

Paul and Barnabas based their case on the empirical evidence of Gentiles who were saved (“converted”) and had not been circumcised. Instead of emphasizing the teaching of Moses, they pointed to current events. (I wonder which side I would have taken because I deeply believe in the authority of the Bible but also am awed by the amazing and surprising effectiveness of the Holy Spirit.)

With battle lines drawn, the opposing sides argued their cases before a council of the Jerusalem church, which was the ecclesiastical “mother church” and headquarters at the time. The traditionalists insisted that “the Gentiles must be circumcised and required to obey the law of Moses” or they can’t be considered Christians.

The non-traditionalists switched from Paul and Barnabas as their spokesmen and brought in the apostolic heavyweight Peter who said that Gentiles need not heed Old Testament requirements that he and other Jews found burdensome. “No! We believe it is through the grace of our Lord Jesus that we are saved, just as they are,” Peter said. Paul and Barnabas gave their latest missionary report of Gentile conversions, and James, apparently the CEO of the council, added quotes from the Old Testament prophets to bolster the new policy. It all ended up in an official letter detailing the council’s conclusion that circumcision is not a prerequisite of Christian faith.

Most modern evangelicals cheer the outcome. When God’s grace shows results, it is okay to move beyond Old Testament law. We are New Testament Christians. The generous new policy was adopted. Today we have pretty much rejected the new policy and come up with a newer policy that probably wouldn’t have passed the Jerusalem council.

The Jerusalem council policy stated that “it seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us not to burden with anything beyond the following requirements: You are to abstain from food sacrificed to idols, from blood from the meat of strangled animals and from sexual immorality. You will do well to avoid these things.”

Apparently it has seemed good to us to agree with dropping the circumcision mandate but not to keep the food-to-idols and blood-from-meat requirements. We have kept the sexual immorality prohibition but usually not as a pre-condition to salvation.

Our purpose here is not to debate the hermeneutics of Acts 15 but to remember the precedent of believers with strong doctrinal differences coming together in partnership to advance the gospel of Jesus Christ, reach new people and build the Church. It is a stunning example of getting along in spite of differences.

It is a wonderful story followed by the report in Acts 15:36-41 of Christianity’s most famous first missionaries sinking into a comparatively petty personality clash that they couldn’t resolve. In order to visit his home church in Jerusalem, Mark had dropped out of the team that Paul led (Acts 13:13), and Paul was upset with him. When Mark wanted to return to the team (Acts 15:38), Paul wouldn’t forgive and refused to allow Mark back. The rest of the team took sides, and Barnabas founded a new mission with Mark and without Paul.

You would think that Paul would be the first person to give a second chance since the Church gave him a second chance after he persecuted and killed Christians, which seems a whole lot more serious than skipping work to visit home. And, you would think that if they could resolve the major differences over Old Testament law and New Testament grace, they could somehow resolve this minor personality conflict. But, they couldn’t; or at least they didn’t.

I would probably give Paul the benefit of the doubt in his leadership decision if Mark had not gone on to write the second book of our New Testament, The Gospel According of Mark. I know I would not like going down in history as someone who couldn’t get along with the author chosen by God to write the biography of Jesus; after all, this does seem to indicate that John Mark was a responsible person.

Purists or Partners?

Many Christians and especially leaders are forced to choose between purism and partnership. There are good reasons for both.

Purists are people of strong conviction with established traditions and biblical arguments. They rightly quote biblical teachings against unequal yokes with those of different doctrine and practice. Sadly, two millennia of strong personalities have divided churches, started denominations, split missions and broken families. If our purist predecessors fit our mix, we praise them as heroes; if their idea of what is pure seems silly to us, we criticize them as scoundrels.

Partnerships are pursued by people who want to see the greater good of coming together in Christ. They celebrate unity within diversity and quote 1 Corinthians 12:12-13, “The body is a unit, though it is made up of many parts; and though all its parts are many, they form one body. So it is with Christ. For we were all baptized by the one Spirit into one body — whether Jews or Greeks, slave or free — and we were all given the one Spirit to drink.” Sadly, two millennia of strong personalities have too often compromised essential biblical truths, joined bad guys with good guys, and caused calamities.

Think of purism and partnership as wonderful virtues but like the “gutters” on opposite sides of a bowling alley. A gutter ball on either side is a loser. But, as most bowlers know, there is a switch on the control console to lift guardrails to block both gutters. The rails are designed for children and starter-bowlers, but anyone can use them. The rails keep the ball out of the gutters, onto the alley and significantly increase the probability of success. They can be especially helpful for bowlers who have a chronic tilt to their throw that keeps them repeatedly going off into the right or left gutter. And, so it goes for Christians, churches, missions and ministries. Many of us have chronic tilts that throw us off. We need guardrails to keep us out of the gutters.

What about you? Is your standard tilt to be a purist or a partner?

I’ll tell you my answer (which some will identify as idealistic impossibility). I am a purist in that I am committed to the truth and authority of the Bible and hold to the historic Christian faith. I am a Christian, but specifically I am an evangelical Christian who cannot compromise on Scripture, Christ, salvation, evangelism and the Church.

At the same time I am enthusiastic about partnerships. I grieve when I see dogmatic independence over secondary and tertiary issues that keep Christians apart, diminish the reputation of God, decrease evangelism and discipleship, and divide the Church of Jesus Christ. I thrill over reports of churches partnering to serve their communities, missionaries working hand-in-hand with colleagues from competing agencies and denominations seeking to bless and grow other denominations.

As the longtime pastor of a large suburban congregation, I led efforts to start new churches for other denominations. We gave money, leadership and thousands of people to start and grow churches with different labels, governance and modes of baptism but shared essential evangelical faith and doctrine. Yes, I believe we can be purists without becoming extremist, and we can be partners without compromising essential faith.

Exempli Gratia

Writers in English often insert “e.g.” as a way to say “for example” (although probably forgetting that the abbreviation is for the Latin phrase exempli gratia). We all know examples of spiritual and organizational partnerships. Consider a few to prime the pump for ongoing discussions.

Welcoming and Partnering With Immigrants

Evangelical churches in the United States have a long and wonderful history of sending, supporting and praying for missionaries to other countries. I grew up in a large church with the goal of tithing its membership to what was then called foreign missions. Some years the goal was reached: One out of 10 church members were overseas missionaries. Missions and missionaries were woven into sermons, budgets, Sunday school, youth retreats and even real estate (the church bought up homes around the neighborhood to house missionaries on home assignments). But I don’t remember any talk about missionaries from overseas to America. The underlying premise seemed to be that we were senders, and they were receivers and never the other way around.

Today 12.9 percent of the United States population was born outside of the United States. These foreign born number 40 million. While the percentage is not an all-time high, the total number of people is certainly a record high. Unlike other countries with large or growing foreign populations, many have come to America from countries with booming churches, evangelistic zeal and spiritual commitment. They are a new wave of foreign missions — missionaries to the United States from foreign nations. These immigrant missionaries are not only evangelizing, discipling and church planting in America, they are conduits of the gospel, relationships and money back to their homelands — native speakers who are probably quicker and maybe more effective than if American Christians went to their countries.

Here is an unprecedented opportunity for established U.S. churches and Christians to build relationships, learn and be discipled by those God has sent as missionaries to us. This is not a call to internal hegemony or paternalism but to personal, professional, organizational and spiritual partnerships.

There is a biblical precedent. Paul, a native of the eastern Mediterranean, held to a strategy of going where no missionaries had gone before. He had the heart and passion of a pioneer who wanted to start churches where there were no churches. But, he made an exception for Rome. The Roman church was already established. Paul really wanted to see the capital of the empire.

His arrival is chronicled in Acts 28 when the brothers from the Roman church traveled to meet and welcome the missionary from Antioch with a different native tongue and accent. They found him, housed him and supported him. “At the sight of these men Paul thanked God and was encouraged” (Acts 15:15). The rest of the story comes from the rest of the Bible — how the Roman church partnered with Paul and the gospel reached all the way into Caesar’s household.

Following the biblical example, American churches can welcome immigrant missionaries, provide housing, become partners and write a line for today’s book of Acts that “At the sight of evangelical Christians these immigrants thank God and are encouraged.”

Initiating Cooperation, Consortiums and Mergers

There aren’t a lot, but local churches united in support consortiums are champions of partnerships. I know from experience.

Raising financial support is a constant challenge for faithful ministers both serving in the United States and serving other nations. Support raising usually uses “partnership” terminology to describe the relationship between the donor and the recipient.

However, churches and individual Christians can also build partnerships. One consortium of large missions-minded congregations agreed that each one would underwrite up to 25 percent of the total budget for one another’s missionaries. The philosophy of each precluded total support even for one of their own members but a willingness to partner with churches in neighboring towns. Some new missionaries were able to become fully underwritten in weeks instead of years. Of course, denominations are also consortiums with member churches banding together in partnerships. This is very good and powerful. However, there is something uniquely attractive about consortiums of local churches from different denominations partnering to advance the gospel.

While most churches are not able to partner in long-range-support consortiums, most can partner in short-term events. In May 2016 four suburban Minneapolis churches are partnering with International Justice Mission (IJM) to sponsor the Twin Cities Justice Weekend.

Westwood Community Church, Wooddale Church, Christ Presbyterian Church and Grace Church may be described as Baptist, Congregational, Presbyterian and independent. Their missions leaders have partnered to organize learning sessions, worship services, sermons, a large concert and a “Run for Justice” with runners from all four congregations. Initiatives are underway to invite dozens more churches to participate. This is an example of churches having their own events fitting into their own programming plus adding joint events — all around the same themes and all in support of IJM.

The once-upon-a-time Evangelical Foreign Missions Association (EFMA) and the Interdenominational Foreign Missions Association (IFMA) were separate associations with distinctively different member organizations. As a guest speaker at their different conferences I could feel the distinctions but also recognize the evangelical beliefs and vision that were the same.

Merging these two associations into Missio Nexus wasn’t easy with separate histories and leadership, but the uniting has not only been effective but a marvelous example of evangelical partnership — allowing every member to be who they are while partnering together. It is a high standard for members to repeat in their international ministries.

Seeking Common Ground

Some leaders look for differences so they can isolate. Some leaders look for common ground so they can cooperate.

On religious freedom issues there has been frequent cooperation between the National Association of Evangelicals and the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Each organization knows their doctrinal distinctions and neither compromises on their different doctrines. However, they share common ground on religious liberty issues that are clearly connected to each one’s doctrinal commitments to traditional marriage, opposition to abortion-on-demand and ministry to the poor. The common ground has led to partnerships in friend-of-the-court briefs before the U.S. Supreme Court, letters to members of the Congress and public statements.

There will always be critics who disavow any cooperation or even communication with those with whom we have differences and disagreements. However, partnerships can produce otherwise unattainable outcomes that make the criticisms worth it.

How far we are willing to go in seeking common ground for unexpected partnerships depends on the circumstances. During World War II the United States and the United Kingdom brokered alliances with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in order to defeat Germany. Under less threat it would be hard to imagine Franklin Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin agreeing or partnering on much of anything. In this case, their common ground was Adolf Hitler who was their common enemy.

Agreeing to a New Comity

“Comity” is a legal term referring to agreements between courts to respect each other’s jurisdictions. It became a colonial concept as European nations established exclusive regions in Africa, Asia, Latin America and beyond. While most former colonies have long ago become independent, the vestiges of colonial comity are still easy to see — English is spoken in Malawi; Portuguese is spoken in Mozambique; and France sends troops to Mali, the Central African Republic and other Francophone nations.

Comity became a form of partnership among mission agencies that divided up colonial nations, so one agency sent missionaries and established churches in the south while other agencies limited themselves to the north, the west and the east. Similar comity arrangements were established during the expansion of denominations across America’s 18th and 19th century frontiers.

We can debate the pros and cons of comity in missions but agree that comity arrangements were primarily geographical, many worked very well, and they were a form of co-operation and partnership instead of competition and opposition.

Today’s comity is seldom geographical and primarily based on function and expertise. Different organizations have different strengths — church planting; refugee resettlement; broadcasting; education; translation; disability ministries; etc.

Few if any organizations are large enough and have the resources to do everything, so there is a “division of labor” that distributes functions through common agreement. This may connect Pentecostals, cessationists, pedobaptists, Anabaptists, Calvinists, Arminians, denomination agencies, faith missions and independents as partners in the same community but with agreements to specialize in separate but interconnected functions.

Focusing More on Prototypes Than on Protectorates

Copyright law and infringements are a controversial issue in international relations for many reasons. Most international travelers are very familiar with “knock offs” where $500 European designer jeans are copied and sold in a distant country for $25. Yes, there are legitimate claims to intellectual property that must be respected, and the laws must be enforced. However, there are cultural differences underlying the multi-billion dollar competition.

In the industrialized west we have copyright and patent laws to protect the rights and royalties of the original owner. Other cultures view all intellectual property to be held in common by the larger community — to them there is no perceived ethical offense in reproducing someone else’s ideas.

Similar conflicting philosophies come over into ministry initiatives. Do we view what we do as a prototype for others to copy or a protectorate for us to own?

When we truly believe that Christians are partners in world evangelization under the lordship of Jesus Christ, we are pleased if others copy our ideas. We delight when our material is printed by others. We are okay when our creative approach to fundraising spreads to other agencies. Prototyping can win the world; protectorates isolate the gospel.

OPPORTUNITY in all caps

The firing squad of crisis is clearly pointed at our generation. Pick the crisis — civil conflict from Syria to South Sudan; epidemics from Ebola to Zika Virus; terrorism from Paris to San Bernardino; moral changes from human sexuality to political corruption; environmental arguments over climate to oil fracking. These and more shout for our generation’s attention. They also create an unprecedented opportunity for the hope of the gospel.

In his book “The Triumph Of Faith,” Rodney Stark brings a scholar’s documentation and analysis on why the world is more religious than ever. He shows the explosive growth of religion since 1950. Christianity is growing everywhere in first place and is increasing its lead.

Someday in heaven we may be asked what it was like to be Christians in our generation of multiple crises and unprecedented opportunity. My hope is that we will not answer one-at-a-time or stand in isolated groups with names unknown to most of heaven’s population. My hope is that we will stand hand-in-hand to answer as a generation of partners in the name of Jesus Christ.

This article originally appeared in ANTHOLOGY, the magazine of Missio Nexus.

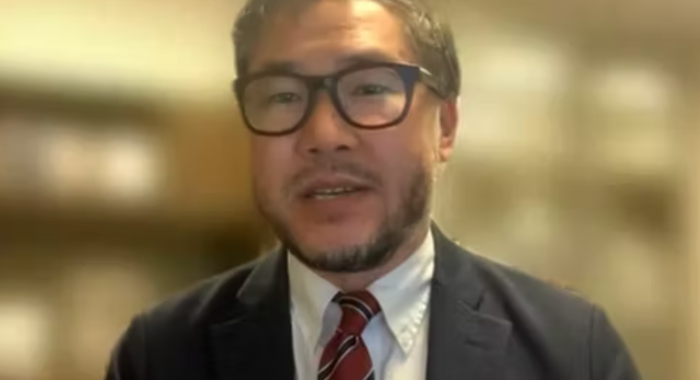

Leith Anderson is president emeritus of the National Association of Evangelicals and pastor emeritus of Wooddale Church in Eden Prairie, Minnesota. He served as NAE president from 2007–2019, after twice serving as interim president. He served as senior pastor of Wooddale Church for 35 years before retiring in 2011. He has been published in many periodicals and has written over 20 books. Anderson has a Doctor of Ministry degree from Fuller Theological Seminary, and is a graduate of Moody Bible Institute, Bradley University and Denver Seminary.

View All Articles

View All Articles